由《前赤壁赋》想到彼埃尔和安德烈在渡口的对话,那是《战争与和平》里最优美的篇章之一。彼埃尔所转述的赫德,在我看来,和苏轼是相似的;不同的是,苏轼和大多数中国人一样,并没有那个“上帝”的概念。

夕阳、渡口、河、朋友、争论,青春洋溢,如在眼前。可是套用安德烈的话:使我信服的不是这个,不是托尔斯泰在这里想说的道理,而是他所描述的生命本身。

王国维感叹说:“哲学上之说,大都可爱者不可信,可信者不可爱。”信夫!

War and Peace, Book 5, Chapter XII

Prince Andrey listened to Pierre's words in silence. Several times he did not catch words from the noise of the wheels, and he asked Pierre to repeat what he had missed. From the peculiar light that glowed in Prince Andrey's eyes, and from his silence, Pierre saw that his words were not in vain, that Prince Andrey would not interrupt him nor laugh at what he said.

They reached a river that had overflowed its banks, and had to cross it by a ferry. While the coach and horses waited they crossed on the ferry. Prince Andrey with his elbow on the rail gazed mutely over the stretch of water shining in the setting sun.

“Well, what do you think about it?” asked Pierre. “Why are you silent?”

“What do I think? I have heard what you say. That's all right,” said Prince Andrey. “But you say, enter into our brotherhood, and we will show you the object of life and the destination of man, and the laws that govern the universe. But who are we? —Men? How do you know it all? Why is it I alone don't see what you see? You see on earth the dominion of good and truth, but I don't see it.”

Pierre interrupted him. “Do you believe in a future life?” he asked.

“In a future life?” repeated Prince Andrey.

But Pierre did not give him time to answer, and took this repetition as a negative reply, the more readily as he knew Prince Andrey's atheistic views in the past. “You say that you can't see the dominion of good and truth on the earth. I have not seen it either, and it cannot be seen if one looks upon our life as the end of everything. On earth, this earth here” (Pierre pointed to the open country), “there is no truth—all is deception and wickedness. But in the world, the whole world, there is a dominion of truth, and we are now the children of earth, but eternally the children of the whole universe. Don't I feel in my soul that I am a part of that vast, harmonious whole? Don't I feel that in that vast, innumerable multitude of beings, in which is made manifest the Godhead, the higher power—what you choose to call it—I constitute one grain, one step upward from lower beings to higher ones? If I see, see clearly that ladder that rises up from the vegetable to man, why should I suppose that ladder breaks off with me and does not go on further and further? I feel that I cannot disappear as nothing does disappear in the universe, that indeed I always shall be and always have been. I feel that beside me, above me, there are spirits, and that in their world there is truth.”

“Yes, that's Herder's theory,” said Prince Andrey. “But it's not that, my dear boy, convinces me; but life and death are what have convinced me. What convinces me is seeing a creature dear to me, and bound up with me, to whom one has done wrong, and hoped to make it right” (Prince Andrey's voice shook and he turned away), “and all at once that creature suffers, is in agony, and ceases to be… What for? It cannot be that there is no answer! And I believe there is… That's what convinces, that's what has convinced me,” said Prince Andrey.

“Just so, just so,” said Pierre; “isn't that the very thing I'm saying?”

“No. I only say that one is convinced of the necessity of a future life, not by argument, but when one goes hand-in-hand with some one, and all at once that some one slips away yonder into nowhere, and you are left facing that abyss and looking down into it. And I have looked into it …”

“Well, that's it then! You know there is a yonder and there is some one. Yonder is the future life; Some One is God.”

Prince Andrey did not answer. The coach and horses had long been taken across to the other bank, and had been put back into the shafts, and the sun had half sunk below the horizon, and the frost of evening was starring the pools at the fording-place; but Pierre and Andrey, to the astonishment of the footmen, coachmen, and ferrymen, still stood in the ferry and were still talking.

“If there is God and there is a future life, then there is truth and there is goodness; and the highest happiness of man consists in striving for their attainment. We must live, we must love, we must believe,” said Pierre, “that we are not only living to-day on this clod of earth, but have lived and will live for ever there in everything” (he pointed to the sky). Prince Andrey stood with his elbow on the rail of the ferry, and as he listened to Pierre he kept his eyes fixed on the red reflection of the sun on the bluish stretch of water. Pierre ceased speaking. There was perfect stillness. The ferry had long since come to a standstill, and only the eddies of the current flapped with a faint sound on the bottom of the ferryboat. It seemed to Prince Andrey that the lapping of the water kept up a refrain to Pierre's words: “It's the truth, believe it.”

Prince Andrey sighed, and with a radiant, childlike, tender look in his eyes glanced at the face of Pierre—flushed and triumphant, though still timidly conscious of his friend's superiority.

“Yes, if only it were so!” he said. “Let us go and get in, though,” added Prince Andrey, and as he got out of the ferry he looked up at the sky, to which Pierre had pointed him, and for the first time since Austerlitz he saw the lofty, eternal sky, as he had seen it lying on the field of Austerlitz, and something that had long been slumbering, something better that had been in him, suddenly awoke with a joyful, youthful feeling in his soul. That feeling vanished as soon as Prince Andrey returned again to the habitual conditions of life, but he knew that that feeling—though he knew not how to develop it—was still within him. Pierre's visit was for Prince Andrey an epoch, from which there began, though outwardly unchanged, a new life in his inner world.

周末和朋友聊起《野鹅敢死队》(The Wild Geese)来,找到这张照片和插曲《Flight of the Wild Geese》。《音频下载》

周末和朋友聊起《野鹅敢死队》(The Wild Geese)来,找到这张照片和插曲《Flight of the Wild Geese》。《音频下载》

The art is a lie that leads us to the truth.

The art is a lie that leads us to the truth.

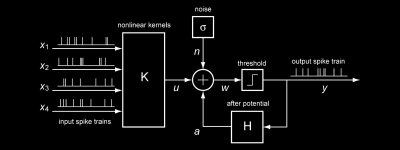

精巧细致(Subtlety)和质朴健壮(Robustness)是矛盾的,做信号处理时常有这感触。一个随便什么的曲线中,哪些成分(Component)是重要的呢?什么分辨率(Resolution)是合适的呢?如何定义价值函数(Cost Function)呢?苹果和桔子的权重(Weight)该如何分配呢?都是些难题啊。

精巧细致(Subtlety)和质朴健壮(Robustness)是矛盾的,做信号处理时常有这感触。一个随便什么的曲线中,哪些成分(Component)是重要的呢?什么分辨率(Resolution)是合适的呢?如何定义价值函数(Cost Function)呢?苹果和桔子的权重(Weight)该如何分配呢?都是些难题啊。