But the preface, which was actually placed in the end of the book in the Chinese edition, is one of my favorite essays. The reason is simple: in its first paragraph, Conan Doyle articulated something I always tried to say.

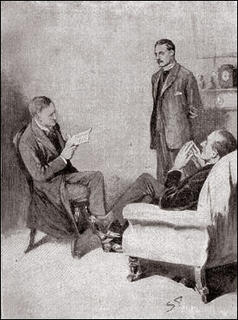

And below is what I got from “Camden House: The Complete Sherlock Holmes”, an excellent Holmes website.

I FEAR that Mr. Sherlock Holmes may become like one of those popular tenors who, having outlived their time, are still tempted to make repeated farewell bows to their indulgent audiences. This must cease and he must go the way of all flesh, material or imaginary. One likes to think that there is some fantastic limbo for the children of imagination, some strange, impossible place where the beaux of Fielding may still make love to the belles of Richardson, where Scott’s heroes still may strut, Dickens’s delightful Cockneys still raise a laugh, and Thackeray’s worldlings continue to carry on their reprehensible careers. Perhaps in some humble corner of such a Valhalla, Sherlock and his Watson may for a time find a place, while some more astute sleuth with some even less astute comrade may fill the stage which they have vacated.

I FEAR that Mr. Sherlock Holmes may become like one of those popular tenors who, having outlived their time, are still tempted to make repeated farewell bows to their indulgent audiences. This must cease and he must go the way of all flesh, material or imaginary. One likes to think that there is some fantastic limbo for the children of imagination, some strange, impossible place where the beaux of Fielding may still make love to the belles of Richardson, where Scott’s heroes still may strut, Dickens’s delightful Cockneys still raise a laugh, and Thackeray’s worldlings continue to carry on their reprehensible careers. Perhaps in some humble corner of such a Valhalla, Sherlock and his Watson may for a time find a place, while some more astute sleuth with some even less astute comrade may fill the stage which they have vacated.His career has been a long one–though it is possible to exaggerate it; decrepit gentlemen who approach me and declare that his adventures formed the reading of their boyhood do not meet the response from me which they seem to expect. One is not anxious to have one’s personal dates handled so unkindly. As a matter of cold fact, Holmes made his debut in A Study in Scarlet and in The Sign of Four, two small booklets which appeared between 1887 and 1889. It was in 1891 that ‘A Scandal in Bohemia,’ the first of the long series of short stories, appeared in The Strand Magazine. The public seemed appreciative and desirous of more, so that from that date, thirty-nine years ago, they have been produced in a broken series which now contains no fewer than fifty-six stories, republished in The Adventures, The Memoirs, The Return, and His Last Bow, and there remain these twelve published during the last few years which are here produced under the title of The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes. He began his adventures in the very heart of the later Victorian era, carried it through the all-too-short reign of Edward, and has managed to hold his own little niche even in these feverish days. Thus it would be true to say that those who first read of him, as young men, have lived to see their own grown-up children following the same adventures in the same magazine. It is a striking example of the patience and loyalty of the British public.

I had fully determined at the conclusion of The Memoirs to bring Holmes to an end, as I felt that my literary energies should not be directed too much into one channel. That pale, clear-cut face and loose-limbed figure were taking up an undue share of my imagination. I did the deed, but fortunately no coroner had pronounced upon the remains, and so, after a long interval, it was not difficult for me to respond to the flattering demand and to explain my rash act away. I have never regretted it, for I have not in actual practice found that these lighter sketches have prevented me from exploring and finding my limitations in such varied branches of literature as history, poetry, historical novels, psychic research, and the drama. Had Holmes never existed I could not have done more, though he may perhaps have stood a little in the way of the recognition of my more serious literary work.

And so, reader, farewell to Sherlock Holmes! I thank you for your past constancy, and can but hope that some return has been made in the shape of that distraction from the worries of life and stimulating change of thought which can only be found in the fairy kingdom of romance.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

我担心福尔摩斯先生也会变得象那些时髦的男高音歌手一样,在人老艺衰之后,还要频频地向宽厚的观众举行告别演出。是该收场了,不管是真人还是虚构的,福尔摩斯不可不退场。有人认为最好是能够有那么一个专门为虚构的人物而设的奇异的阴间——一个奇妙的、不可能存在的地方,在那里,菲尔丁的花花公子仍然可以向理查逊的美貌女郎求爱,司各特的英雄们仍然可以耀武扬威,狄更斯的欢乐的伦敦佬仍然在插科打诨,萨克雷的市侩们则照旧胡作非为。说不定就在这样一个神殿的某一偏僻的角落里,福尔摩斯和他的华生医生也许暂时可以找到一席之地,而把他们原先占据的舞台出让给某一个更精明的侦探和某一个更缺心眼儿的伙伴。

我担心福尔摩斯先生也会变得象那些时髦的男高音歌手一样,在人老艺衰之后,还要频频地向宽厚的观众举行告别演出。是该收场了,不管是真人还是虚构的,福尔摩斯不可不退场。有人认为最好是能够有那么一个专门为虚构的人物而设的奇异的阴间——一个奇妙的、不可能存在的地方,在那里,菲尔丁的花花公子仍然可以向理查逊的美貌女郎求爱,司各特的英雄们仍然可以耀武扬威,狄更斯的欢乐的伦敦佬仍然在插科打诨,萨克雷的市侩们则照旧胡作非为。说不定就在这样一个神殿的某一偏僻的角落里,福尔摩斯和他的华生医生也许暂时可以找到一席之地,而把他们原先占据的舞台出让给某一个更精明的侦探和某一个更缺心眼儿的伙伴。福尔摩斯的事业已经有不少个年头儿了,这样说可能是夸张了一些。要是一些老先生们跑来对我说,他们儿童时代的读物就是福尔摩斯侦探案的话,那是不会得到我的恭维的。谁也不乐意把关乎个人年纪的事情这样地叫人任意编排。冷酷的事实是,福尔摩斯是在《血字的研究》和《四签名》里初露头角的,那是一八八七年和一八八九年之间出版的两本小书。此后问世的一系列短篇故事,头一篇叫做《波希米亚丑闻》,一八九一年发表在《海滨杂志》上。书出之后,似乎颇受欢迎,索求日增。于是自那以后,三十九年来断断续续所写的故事,迄今已不下于五十六七,编集为《冒险史》、《回忆录》、《归来记》和《最后致意》。其中近几年出版的最后这十二篇,现在收编为《新探案》。福尔摩斯开始他的探案生涯是在维多利亚朝晚期的中叶,中经短促的爱德华时期。即使在那个狂风暴雨的多事之秋,他也不曾中断他自己的事业。因此之故,要是我们说,当初阅读这些小说的青年现在又看到他们的成年子女在同一杂志上阅读同一侦探的故事,也不为过。于此也就可见不列颠公众的耐心与忠实之一斑了。

在写完《回忆录》之后我下定决心结束福尔摩斯的生命,因为我感到不能使我的文学生涯完全纳入一条单轨。这位面颊苍白严峻、四肢懒散的人物,把我的想象力占去了不应有的比例。于是我就这么结果了他。幸亏没有验尸官来检验他的尸体,所以,在事隔颇久以后,我还能不太费力地响应读者的要求,把我当初的鲁莽行为一推了事。对于重修旧业我倒并不后悔,因为在实际上我并没有发现写这些轻松故事妨碍了我钻研历史、诗歌、历史小说、心理学以及戏剧等等多样的文学形式,并在这些钻研之中认识到我的才力之有限。要是福尔摩斯压根儿就没存在过的话,我也未必能有更大的成就,只不过他的存在可能有点妨碍人家看到我其它严肃的文学著作而已。

所以,读者们,还是让福尔摩斯与诸位告别吧!我对诸君以往给我的信任无限感激,在此谨希望我赠给的消遣良法可以报答诸君,因为小说幻境乃是避世消愁的唯一途径。

阿瑟•柯南•道尔谨启

4 comments:

the translation was so terrific. It fully captured the virtue of the oringinal. Among the previous generation of translators, there are quite a few who are truly exceptional. As deceased novelist Wang Xiaobo once confessed he learned his chinese writing from the translated literatures.

... and these translations often remain relatively unfamous.

I was so impressed by the Chinese translation and kept wondering what its English original was ... especially the phrases such as "狂风暴雨的多事之秋","小说幻境乃是避世消愁的唯一途径", "司各特的英雄们仍然可以耀武扬威", and "狄更斯的欢乐的伦敦佬仍然在插科打诨" ...

What makes me worry is that the era of really great translators have seemed past. This seems to be a more traditional translation and i can picture those great masters who dealt with the subject with their strict training, in-depth understanding and mastery grasp of both launguages as well as their focus and responsibility to the writer and readers, which can not be rivaled by today's new comers. I feel lucky that we were able to enjoy the good works growing up. And I worry the newer works can not be introduced with comparable quality thus can give the original work less credit than it deserve or even damage it during the process. Wang Yong Nian for Borges; Fu Lei for Shakespear...

I'd like to add 李丹 for Les Misérables. I loved his translations so much ...

Post a Comment